Stephan Plank – Resetting The Preset

by Jay Sandwich

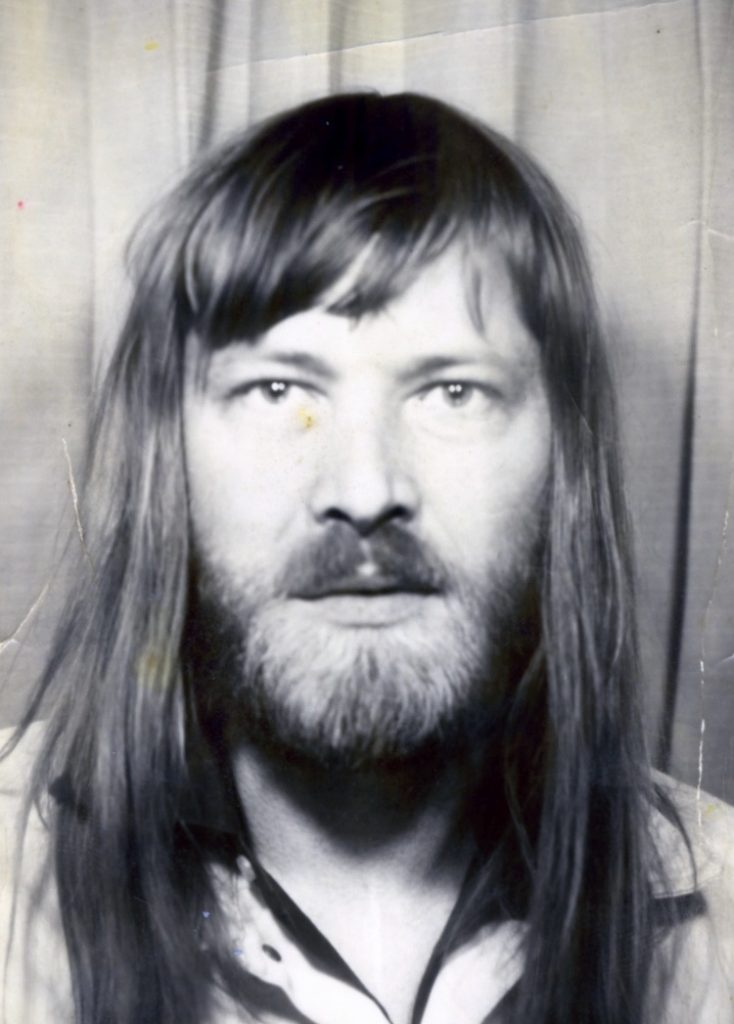

Not many people get to say their dad was a “super-producer”, but in the case of Stephan Plank, son of Conny Plank, it turns out to be true.

Who Is Conny Plank?

While “super-producer” might seem a rather nebulous term to apply to someone, it’s hard to think of a better-fitting way to describe Conny Plank, considering that musicians from around the world to record with him at his abode in Germany, where he had his studio for many years.

Many might call Rick Rubin, or Mutt Lange, two of rock’s big super-producers. Producers like Timbaland or Dr. Dre may have been referred to in such a way as well. Of course, what makes each of these producers “super” is different from one another, as they all have their fortes.

Conny Plank, and his motives for making music at the time that he was fervently doing so, are altogether different again from all the rest.

Conny, in his own way, is surely in the same stratum of certain legendary names in the music business, except he is less associated with mainstream music, never aiming for fame and glory so much as experimentation and purity of sound, so he has, as a result of not playing “the game”, a bit more mystique surrounding him, and credibility as an artist for endless miles.

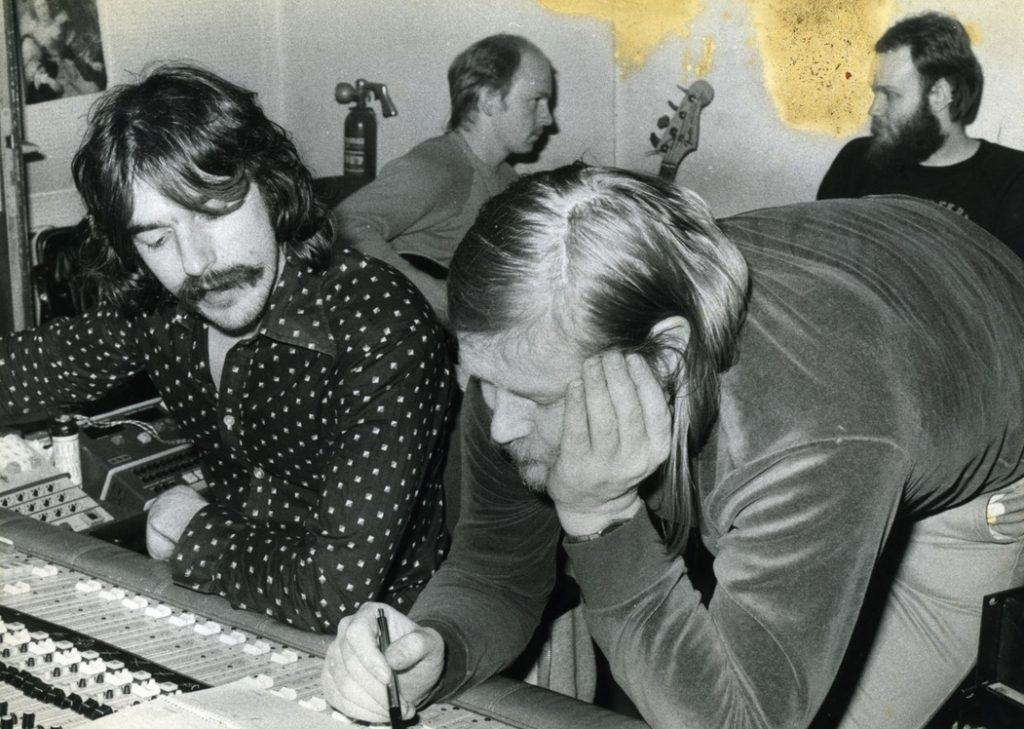

In his home studio, Conny recorded some of the most sonically expressive, idiosyncratic, and experimental recordings ever to be pressed to vinyl, including many great krautrock albums by the likes of Neu!, Kraftwerk, Guru Guru, Night Sun, Can, and many more, some of whom were native to Germany.

Here’s an example of one of the many ground-breaking albums that Conny worked on, by Cluster (formerly Kluster). It is but one in an long lineage of albums with Conny Plank’s unique stamp of sonic engineering wizardry.

In addition to having a big impact on Krautrock and rock in general, Conny Plank was responsible for some of the earliest “ambient” albums (before the term was coined for such music) as Cluster & Eno, Kraftwerk’s Autobahn, and his wife Christa Fast even sang on Music For Airports by Eno, which could be considered one of the first, if not “the” first, album of this kind.

Conny recorded with many musicians who made their way to his studio from all corners of the globe, and then, from there, these musicians went on to have a deep and lasting impact on music and future musicians.

I’m referring to the likes of Devo in their early years, as well as the Eurythmics, Ultravox, Killing Joke, The Meteors, Kraan, Hunters & Collectors, A Flock of Seagulls, and dozens more artists, some more obscure, some more well-known.

One might wonder how Conny Plank was able to have such a prolific output for so many years and still manage to capture so much lightning in a bottle. To many, it is still somewhat of a mystery, and understandably so.

The recording of various artists went on until Conny’s untimely death in 1987 of laryngeal cancer.

Conny’s Son, Stephan Plank

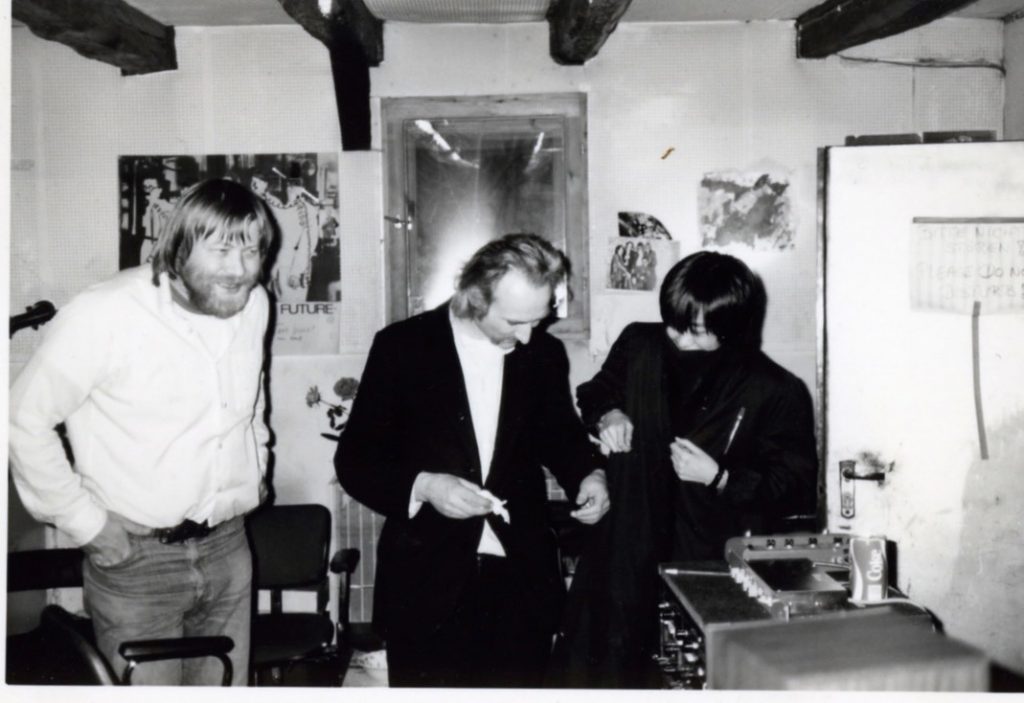

While Conny lived, he worked tirelessly with band after band at his home studio, while his wife and only son watched him work, and provided a home life, if a somewhat unconventional one.

His son, Stephan, grew up in an atmosphere both strange and interesting, making playmates out of some of the odd house guests who would arrive, stay a while, and then eventually leave, perhaps never to return.

When Conny died suddenly in December of 1987, it was difficult for anyone to process; most of all his family, who was used to Conny being a rather indomitable spirit. Now he was gone.

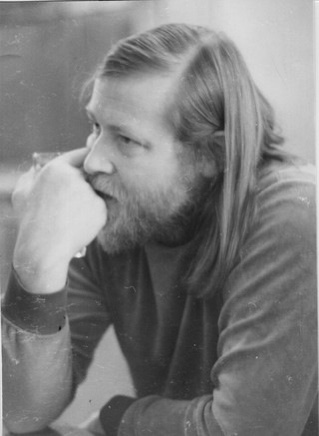

Stephan was barely a teenager when Conny died, and so it took him a long time to process his death, and reach any kind of closure.

Indeed, it wasn’t until his 40’s that Stephan finally had the urge to look back at who Conny was, and make sense of his legacy as a creative force in the music industry.

This reflection lead him to the creation of his own documentary, called The Potential of Noise, which features interviews with a slew of musicians who knew Conny best, from working with him in the studio.

Here’s a trailer for the documentary, The Potential of Noise.

I caught up with Stephan on October 1st, 2019, to ask him questions about the documentary, his father and his music, and what his life his like now.

Interview

YC: Why did you make this documentary?

SP: In a sense, I was liberating myself of my father. I was 13 when my father died, and I grew up in the music industry. My mother then continued renting out the studio, and soon people were approaching me saying, “You’re the son of Conny, wow!” and I would think to myself, “…but I don’t know what he did. How should I reply to this?”

In a way, I made this film to clear this up this mystery, and give myself a chance to talk about it, and also reach a better understanding of my father.

YC: Did you know about his impact at that time?

SP: I suspected the impact. Growing up in the studio, all the people knowing about it…for me, it was not knowing what a producer did and how he worked that bugged me.”

YC: So you didn’t really know this – the extent of Conny’s influence – until you started making the documentary?

SP: Yes and no, growing up in the studio, I had seen how producers worked with different bands, but i didn’t know how Conny worked with bands and how he liberated their thinking. The interesting thing about the work of my father was that he did a lot of “first” albums, so he was an integral part in constituting the bands avatars or egos where his own ego became fused with the bands’ ego.

YC: Were musicians and bands just randomly coming to his studio, or did he somehow advertise for musicians to come to see him?

SP: His records were his calling cards. Lots of people at this time who were looking for a producer, would look at their record collection, and see that Conny had made many of their favourite albums, so they would come because of this.

YC: Was this localized to your area of Germany or were people coming from all over the world?

SP: Everywhere. For instance, Devo from America, Hunters & Collectors from Australia, and many others from around the world…they would hear something like Kraftwerk and Neu! and they wanted to come see him and learn his methods.

He was a lightning rod for bands who wanted to approach music differently. For instance, Devo first wanted to work with David Bowie, and then Brian Eno, who was a friend and frequent collaborator with Conny, so he brought Devo with him to visit Conny.

Ultimately, Brian Eno was thinking to shape Devo to be a little more pretty-sounding, but when Devo realized that Conny was like-minded to them in terms of anti-melody and embracing noise, they decided to work with him instead.

YC: How did Conny come to know Brian Eno?

SP: This was through Neu! that he met Brian, who came to our farmhouse to work on Music For Airports, which featured my mom singing some of the vocals on that album.

YC: All this happened obviously after Brian Eno’s Roxy Music days, but how was the connection made?

SP: Brian Eno heard Conny’s work through Neu!’s first album, which had an appeal to many British musicians. Some of these new Krautrock sounds that my dad was making were very interesting to many British musicians who were looking for a new type of sound at this time.

These Krautrock albums weren’t about “hit” singles, but more about a new mentality towards music. For instance, Michael Rother was in Kraftwerk and Neu!, and collaborated with Cluster, which lead him to Eno, and Music for Airports.

YC: There was not much like Eno’s Music For Airports at the time, really, right? This was a truly groundbreaking album.

SP: If anyone should be found guilty of launching “ambient” music, it should be Brian Eno and Michael Rother.

YC: Did you or do you now listen to any ambient music yourself?

SP: I listened to a lot of it growing up, and I think it’s very interesting to see how it all started. My father was born in 1940 and he grew up in the time of the 2nd World War.

He grew up in Kaiserslautern, or K-town, and this was a place which featured a lot of troop entertainment. My father was friends with a couple of G.I.’s so they’d take him to see some of this entertainment. There is a term in German – “icht” – and he said he was icht when he listened to this troop entertainment.

YC: So he appreciated this type of music a great deal.

SP: Yes, a lot. He loved big band music like Duke Ellington. There is actually a story about Duke Ellington involving my father, where Duke Ellington came to Cologne to do a concert, and he needed a rehearsal space, and my dad didn’t have his recording studio at the time (because he wasn’t yet a sound engineer), but he was working in one.

He asked the studio owner if he could have the Duke come to the studio and rehearse. Conny happened to be able to record this session, and then when Duke finished, he asked my father if he could hear the recording he made of his band, and when he heard it, he told him that he was doing “good sound” and that he liked what he heard.

This was the point where my father heard his hero say he was doing a good job, and then he felt like he could be a sound engineer – this encounter boosted his confidence. I wasn’t sure i this was a tall tale or not, because these things can be exaggerated, but then I went through the archive of our studio, and I found the Duke Ellington tape, which I then made into a vinyl release, and this is now available.

YC: When was this released?

SP: 4 years ago now.

YC: Did it see a big release?

SP: We released it worldwide, but the audience for obscure Duke Ellington releases now is a very specific group of music fans. Some people have even called me to tell me jokingly that Duke Ellington sounds even a bit Kraut-y on this release.

YC: Is there any truth to that? Does it sound sort of Kraut-y?

SP: I can’t hear it, but I like the idea.

YC: This would have been at the beginning of Conny’s career, and the end of Duke’s?

SP: Yes. This was recorded July 9th, 1970. Now it is available on Spotify.

YC: Ok, well I’ll have to check that out. So, once the studio became active and Conny had gone into the business of sound engineering more officially, at this point you were just there running around, being a kid. Did you think the environment you lived in was normal?

SP: Everything your parents do seems normal to you, because at first you have nothing to compare it to. For me, these slightly strange guests being around all the time was normal to me. And, as musicians are, they were very playful people, so they made good playmates for me.

YC: And these musicians would stay there for days, or weeks, while your dad worked in his studio?

SP: Yes, he worked constantly.

YC: Did you see him much?

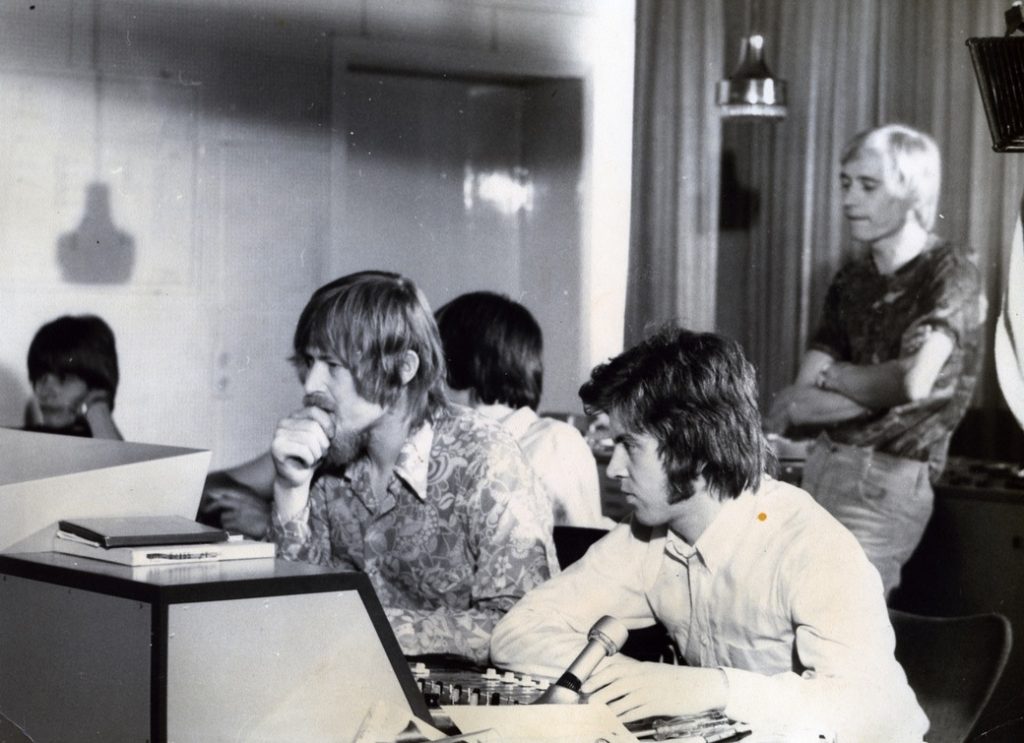

SP: Well, he was right next door, but it was clear that this is where the big boys played. You have to realize, this was a time before digital looping was possible.

So they had to use tape loops, so they’d be setting up microphone stands all over the studio, which was very interesting-looking to a 5-year-old. So I wasn’t allowed to touch anything, or their work could be destroyed. Therefore, I wasn’t allowed in very often, or very rarely.

YC: At what point did you realize what was going on in there?

SP: Between 10-12 years old, I started to understand the concept of work. But there was no time to really ask my dad about the finer details of his work.

At that time, it just made more sense for him to focus on his work, rather than explain everything to me. I was aware that something interesting was happening, and I was aware that people wanted to meet my father, or to see some of the famous musicians who came there, like the Eurythmics, and to get their autograph. To me these were just normal people working with my father, not stars.

YC: Were you an only child?

SP: Yes.

YC: So were you very well-behaved then, or more of a brat?

SP: I was basically a brat. I was fighting for the attention of my parents. By the time I was becoming a teenager, although we did not know it, my father had cancer, and would die soon. He died December 6, 1987.

At the start of 1987, around Easter holidays, we went with the Eurythmics to records their Japan Live tour. I was taken along, because my father was very aware that his time with his family was becoming limited. Still, he was working like a madman.

YC: At what point did you realize he was nearing the end of his life?

SP: My parents were optimistic until the last second. I remember I was with some friends, because my father with in the hospital again, and on that Sunday I got a call saying my father had died, and so I came to the hospital to see my mother and brother. It was horrible.

YC: What happened next?

SP: My mother continued to rent out the home studio, and musicians continued to come there to record. It was a nice place, and had a lot of analog gear, and so it was still very attractive to musicians to come there.

Recording studios can often be a stressful place for musicians, because they may have gotten a record deal, and suddenly the pressure is on to make their greatest music in a limited amount of time. In other words, they would feel like the meter was running.

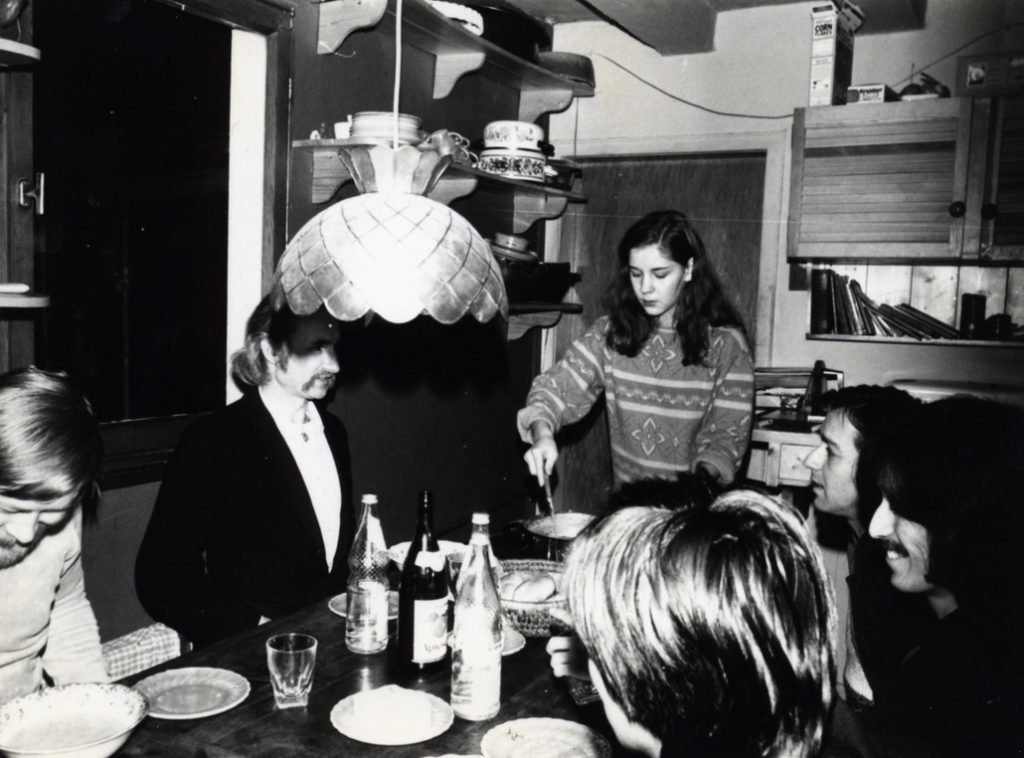

My father and my mother together built this place to ease musicians of this feeling. It wasn’t a fancy place. It appeared a little bit squalid, but this was by design, because it would release some of the musicians’ tensions about being in a studio in the first place.

And then, musicians could let go and really inhabit the music they were making.

YC: Was Conny a fan of live-off-the-floor recording? Is that the scenario musicians were in at his studio?

SP: Conny was a fan of live recording, and he had some movable walls on wheels which he could turn and move so musicians could see each other. He was also very adamant that bands recorded their first version of a song live.

They could do overdubs after, but the live feeling had to be captured. And he was very avid about sound quality. There was a particular way the my father liked the cords in his studio, to be the exact right length with no cable wasted or lying on the floor tangled up.

YC: He was just very organized with his cables?

SP: This was the magic of my father, the way he made the musicians less aware of the recording process just by arranging the cables in a particular way. My father’s goal was to help musicians to let go during their performance, and then he would catch these results, and he made it all seem easy.

YC: I guess Conny was always listening and tuned to the music even if the band didn’t think he was?

SP: Yes, Conny seemed relaxed and the band would also be relaxed, but if he heard a synthesizer reach a point where he knew it was the perfect tone for the song, he would stop the band and tell them to make sure to leave that synth at that setting, because he knew it sounded great.

He would say “Stop, don’t touch the knob again. You are precisely at the hot moment!” In other words, he could always recognize when the band was at the peak of their performance.

He wasn’t trying to force them to get there, but when they got there, he knew. If a band was not getting better as they continued, he knew they’d reached their peak at that point.

He was simply good at hearing when a band was playing their best, or if something special was happening.

YC: So he didn’t intimidate anyone like some producers might?

SP: My father was a little bit like a psychologist, who would ask you questions, and then not tell you anything. He was able to get a band to think about a concept, and then they would get ideas based on what he said.

He didn’t need to tell them anything, just get them thinking about things they weren’t thinking about before. This way, they could conceive an original idea.

YC: Was he trying to guide them, or manoeuvre these bands?

SP: He wasn’t trying to control them. He was just trying to get them to think about what they might want to become, but he didn’t tell them what was, because he himself didn’t know.

YC: Would you say most bands liked his methods as a producer? Were there any bands who didn’t appreciate his methods and left the studio?

SP: Most bands did like his methods, and after his death, he became more of a superhero of german production, and so it was hard to find anyone who would say anything remotely negative about him.

This is why I was thankful to Holger Czukay, who told me “Well, he probably wasn’t the perfect father…” Most people treated him, in the interviews, in a very reverent way, but Holger had the guts to just say exactly what he thought, the way he experienced it.

YC: Why did Holger do that?

SP: Well, Can and Holger were all about authenticity, and Holger realized who was asking him, and to be true, he had to say it like he felt it. He was afraid of nothing, basically, and you learn to live with the consequences.

YC: Did he witness it personally or was he just speculating?

SP: Holger just saw that it was him and my father, and then me and my mother. He knew the band was disturbing family time, but he also knew he wanted to do it because it was so much fun.

YC: How are you now with work? Has any of your father’s famous work ethic affected how you approach work?

SP: I feel like my parents gave me a gift. We all seem to rebel against our parents in some way, and luckily, I am able to rebel by reading night time stories to my daughters every night.

YC: So you are reacting to your parents mistakes in some way?

SP: Yes, I feel like we all, as parents, try to not make the same mistakes as our parents, but mistakes are unavoidable, so even if we avoid some of their mistakes, we will make new, original mistakes.

YC: Are there any qualities of your father you feel like you do exhibit?

SP: Well, I am still quite obsessive, especially with my work, but the fun thing about making this film was to see how my father became almost a spiritual father to some of these bands, because whereas their parents may no have been pleased that they were pursuing music as a career, my father was always very supportive, telling them how amazing he thought they were.

He said “Let’s make this great!” and they would accept him as a father figure. Whodini came to see my father from New York, and they met him, and they met me, and they told me they felt like I was their little brother. So, in a way, the interaction at the studio was one big family.

YC: Was there ever any band that your father didn’t particularly want to work with?

SP: He refused to work with U2.

YC: Why, because he didn’t like their music?

SP: My father said that he worked best as a medium between the artist and the tape. And he wouldn’t know what kind of consciousness he’d have to transfer with Mr. Bono.

YC: What does this mean?

SP: I can only say his words, I don’t know. I just think it’s interesting he called him Mr. Bono.

YC: Well it sounds like maybe your father couldn’t relate to the way that U2 approached him?

SP: Maybe.

YC: Conny obviously had his own specific tastes when it came to sounds he liked, and he also helped to define certain tastes as well.

SP: Yes, and when he died, his life’s work was not compromised. He never reached a stage where he had to make recordings to make ends meet. He was 47 when he died, so this was early enough that he had yet to make any compromises.

YC: Basically it’s fair to say everything was going well and then he met an untimely end due to unexpected health issues.

SP: Yes. Conny is a bit of a mystery because most producers focus on one particular sound, but Conny’s favourite flavour was innovation, and he was thinking in terms of “If this is innovative, I will do it…”

YC: What became of all of his gear, like that mixing desk he made?

SP: It’s in London, and still earning its money at the moment. The last Franz Ferdinand and Hot Chip albums were recorded with it, so it’s still in use, with Dave Allan. I had the choice to put it in a museum, or I could give it to someone to work with it. So I chose to find someone who would use it.

YC: Was it a sentimental thing to have to take the rest of his studio apart?

SP: It was done out of need. When Conny died, we were 4 million euros in debt, and, in 2005, when my mother fell ill, we were 400 000 euros in debt. She somehow managed to fall out of the German health care system, so I had to pay for fixing her brain tumour in cash.

So things needed to be sold, and it eventually was mostly sold. There’s a shop in Hamburg, Germany, and it still has some of my dad’s gear, including our Hammond B5. Sometimes people want to buy it, and I will talk to them. If they are good people, I will sell it to them.

My father was never the sum of his equipment, but he was the sum of the ideas he planted in other musicians minds, which means he’s still out there in a way. I think that today my father’s idea of a nice setup might be a nice laptop, and some good converters.

He’d probably travel with a flight case. He might even have been glad to get rid of the studio eventually, because, to be honest, maintaining all of that analog gear can be a pain in the ass. You constantly need to tinker with it to keep it running.

YC: Like you said, he was into innovation, so he probably would have embraced phones and computers fully.

SP: My dad was really into technology, and he bought the first Macintosh computer available.

He bought it under the impression that he could record a musician in New York, and the quality would be good, which obviously wasn’t the case, but at that stage, people told him it would be possible. He was really on the cutting edge, always curious about it.

He had the first emulator, and he always said stuff like “Reset The Preset” to get the machines to go to the fringe places, the red part of the meter so it would groan a little bit. What happens when you get to the place where they’re not supposed to be.

YC: What would he think of the crappy production work out there today?

SP: He always liked well-produced music, and hated badly made music. I think the ratio of good to badly produced music has always been about the same.

YC: So he wasn’t really a snob then?

SP: No, not at all. There a german tradition called Karneval which is 4 weeks before easter. It’s a very christian / catholic thing, where everyone dresses funny and gets blind drunk.

There is a certain kind of music which goes with it. Very basic, in a good way. Conny loved the authenticity of it. He recorded Bläck Fööss, who only did carnival music. He really loved this music.

YC: It sounds like German party music… like polka?

SP: Yes. He loved the identity-finding moments, and he liked Europe a lot – the idea of it. Many bands from Europe would come to him and try to record something in English, and he would try to encourage them to sing in their own language.

These bands give identity to a whole country. When my dad had bands recording at our home, we would sit down to eat dinner, and I remember one of the sins was when a band said they wanted to sound like another band. This was not cool. My dad would say you are not born to be a copy.

YC: What would your dad do if a band really wanted to sound like another band in the studio while they were recording?

SP: Conny was very good at figuring out if a band wanted to sound like another band before they came in, and then pre-emptively not work with them. His goal was originality over anything else.

YC: Yes, which is why I like many of the bands your father had worked with – so many original bands. I was surprised at how many of these exceptional bands there were, when I saw the documentary you made.

SP: As a producer, Conny was very ego-less. Many producers have their particular flavour that they give to a band. Conny was called “Mr. Sound”, because his flavour was that the band sound like the band.

He said that every band gets the sound they deserve. My father really loved Prince, and his album Dirty Mind, and one of the musicians who came to the studio said he wanted to sound like Prince.

So my father said, if you want to sound like Prince, you need to sing like Prince. This musician really couldn’t pull of Prince.

YC: What is your job now?

SP: I do management for Nina Hagen and I’m making 2 more films. One is a documentary called The Truth About The Truth.

YC: Sounds cryptic, what’s it about?

SP: In your brain you have two buckets, one which holds information and one which holds truth. There’s a switch in your brain that decides where it goes. If the info gets into the truth bucket, we’ll be able to debate about it. I want to make a documentary about this mechanism that decides this.

YC: How’d you think of this idea?

SP: There’s a german word “zeitgeist”. In a way, this idea has been explored a lot already. Ad companies think they know how to implant the truth in someone’s mind, and I think that it’s interesting to make people more aware that someone is trying to do this.

I am working with Reto Caduff again, and we are currently gathering funds to help make the movie happen. I also have a start up company that I co founded called Re2you and we are trying to liberate people from technology, since Google and Apple sit on top of all the ecosystems. So we want to emancipate people from this.

YC: All that sounds good and I look forward to seeing the new films when they arrive. Thanks for chatting with me!

SP: Thank you!

Thanks for reading, if you have any comments or questions, pose them below!

|

|

|

|

About Jay Sandwich

Jay is an ex-shred guitar player and current modular synth noodler from a small town somewhere. Quote: “I’m a salty old sandwich with a perspective as fresh as bread.” No bull.

Leave a Reply

Check for FREE Gifts. Or latest free acoustic guitars from our shop.

Remove Ad block to reveal all the rewards. Once done, hit a button below

|

|

|

|